|

|

BMe Research Grant |

|

Pál Csonka Doctoral School of Architecture

Department: Department of History of Architecture and Monument Preservation

Supervisor: Dr. Rabb Péter

Architectural Historical and Constructional Contributions for the Identification of Ottoman Monuments

Introducing the research area

Despite the fact that thousands of buildings of high importance have been emerged during the classical period of the Ottoman architecture in the 16th Century, only a small amount of drawings used in their constructions have survived to our present days. Therefore, the architectural historiography mainly relies on data provided by written documents: accounts and records; buildings and architectural elements which have been excavated by archaeological research. Consequently, the aim of the present research is to reconstruct the spatial and structural principles and the method of documentation of the 15–16th Century Ottoman architecture. This methodology is important not only for the history of the Ottoman architecture, but also provides contribution to the identification and reconstruction of Ottoman buildings located in the territory of Hungary.

Brief introduction of the research place

My research was carried out at the Department of History of Architecture and Monument Preservation, Faculty of Architecture, Budapest University of Technology and Economics. The research work of the Department is supported by nearly 20,000 volumes of handbooks, with significant archival sources and architectural drawings. Besides, the true to form survey of the monuments were carried out with manual and, digital TLS equipment, supported by the Presidency of Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TIKA).

History and context of the research

The history of research and protection of Ottoman-Turkish Art dates back to the turn of the 20th century. The protection of the Ottoman architectural heritage in the territory of Hungary can be divided into three periods: the initial period of the early 20th century, the period of the change of paradigm in the 1960’s, when a specific research of the Ottoman heritage started. This period influences the tendencies of our present days, too, in a more comprehensive international context. In fact, Hungary has played historically a fundamental role in the research of the Ottoman Turkish historiography and architectural history according to the renowned researchers Ármin Vámbéry, Gyula Németh, Lajos Fekete, Ernő Foerk, and Győző Gerő. [S1]

On one side, the actuality of the Ottoman-Turkish architectural research is underlined by the governmental degree published at the end of 2017 (1995/2017 (XII. 19.)) specifically claiming the need for a strategy for the preservation of Ottoman-Turkish cultural values in the territory of Hungary. On the other side, international monument preservation projects have been launched over the last years. The most significant such project was the complex restoration of the shrine of Gül Baba and its surroundings finished in 2018. The exemplary international cooperation also demonstrates intent to protect and restore other Ottoman monuments in Hungary. [S2]

Besides the actuality, it is important to emphasize the universality of the topic. The buildings were constructed in a boundary situation both in spatial and cultural terms, providing a broader context for a group of building in the territory of Hungary to draw general conclusions in the area covered by the former Ottoman Empire.

The research goals, open questions

Only a marginally low amount of drawn documents of the classical Ottoman buildings have remained to our present days, moreover, no drawing remained from the territory of Hungary at all. Therefore, only written documentations of the remains of the buildings are available for the research. Yet, written sources claim that drawings did exist. [1] One of the aims of my research is to reconstruct the nature of these former drawing documents.

In the case of some types of Ottoman buildings, it can be stated that in the composition redactional correspondences exist. The most typical example is the case of minarets, since there is a correlation between the horizontal and vertical dimensions of each structural element. This provides the option to generate the mass of the building algorithmically from the plan.

The aim of the research is to reconstruct the Ottoman design, spatial and structural construction process in the 16-17th Centuries. I would like to answer questions like, by which scale system the Ottoman buildings were made? Is there any correspondence between spatial and structural formation? What are the connections between the buildings in the territory of Hungary and the other peripheral and central areas? Are there any principles that can be generally considered in the Ottoman architectural and structural practices? There are many Ottoman buildings and constructional elements in Hungary that are under investigation and still have to be identified. A further aim of the research is to find architectural regularities that can contribute to the identification and theoretical reconstruction of these buildings.

Methods

The research is based on the examination of manual survey and digital TLS scanner true to form survey documentation of the Ottoman shrines which still exist in the territory of Hungary as well as archival drawings and records from the 15th century of the Topkapi Palace Museum Archives in Istanbul, commands and written resources in the Ottoman Archives of the Republic of Turkey. Using the aforementioned data, a methodology was set up based on surveys that use archive resources and buildings as the primary source, which unites the dimensions measured on buildings, structural features, archival sources, and the method of documentation in the 15–16th centuries and a historical unit of measure. The methodology can serve as an architectural contribution for identifying remains of still unexplored constructional elements of Ottoman shrines.

During the research, true to form survey drawings were prepared about the shrines which are still standing in the territory of Hungary. Besides, the research is based on Hungarian and Ottoman archival sources (Database of Balassa Bálint Museum in Esztergom, Archives of Budapest University of Technology and Economics, The Drawing and Plan Archives of Budapest University of Technology and Economics – Department of Architectural History and Monument Preservation, Plan Archives of Gyula Forster National Heritage and Asset Management Centre, Hungarian Academy of Arts Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Documentation Centre, Hungarian National Archives, Republic of Turkey Prime Ministry Ottoman Archives (T.C. Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi), Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism – Presidency of Cultural Asset and Museums – Office of Monument Preservation in Edirne (T.C. Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı, Kültür Varlıkları ve Müzeler Genel Müdürlüğü, Kurullar Dairesi Başkanlığı, Edirne Koruma Kurulu), Archives of Topkapi Palace Museum (Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi Arşivi), as well as Turkish, Hungarian and English literature.

One of the two most important primary historical sources used is the biography of Mehmet aga, the chief architect of the Ottoman Empire between 1060 and (approx.) 1623. The document is dated from 1614-15 AD. The document consists of several chapters: the first records the life of Mehmet aga, the second details the list of works, the third chapter is about the units of measurement and architectural geometry, and the fourth is about building materials and architectural concepts, in Persian, Arabic and Turkish, therefore the document provides essential contribution of the Ottoman construction methods of 16-17th Centuries. [2] The other important document is a rare 15th Century historical plan from the archives of the Topkapi Palace Museum, which depicts three versions of the shrine of Abdal Ata, Emir Seyyid, Redjeb and Burhan (Bermekan) Dede. Source: [3], published: [4]; [5]; [6].

Results

It can be concluded that the characteristic dimensions of Ottoman shrines that are still visible in Hungary, are also proportional. Similarly, both the horizontal and vertical dimensions of their interior spaces and their structural dimensions can be expressed as an integral multiple of the general architectural measure of the 16th century (bennāʾ arşunı /mimarî arşın).

The arşın (cubit, zira’) is a typical unit of classical Ottoman architecture, existed in with two forms: one used in architecture and another applied in textile measurements. The aşın used in architecture corresponds to 0.758 meters. Regarding the use of the arşın in the architecture of the 16–17th centuries, among other sources, it was reported by the tezkere (script) of Mehmet Aga, who served as imperial architect between 1606–1623. [2] Traditionally, this measure was divided as follows: 1 arşın (zira) = 24 parmaks or barmaks (fingers - inches) = 12 x 24 hats (lines, traits) = 288 x 2 noktas (dots) = 0.775774 meters.

The TLS scanner survey confirms that in the case of the Ottoman shrines in Hungary, the exact structural and spatial dimensions was determined by the system of units used in Ottoman architectural practice of the 15–16th centuries.

The dimensions of the interior space of the octagonal Ottoman shrines in Hungary, measured in a horizontal plane, are the same: 8x8 arşıns. Vertical dimensions include 1 arsin difference: while the Shrine of Gül Baba in Buda has an internal size of 10 (the horizontal and vertical dimensions are the same), the interior of Idris Baba’s shrine is 11 arşıns, although the latter has two horizontal rows of windows. The structural and spatial dimensions of buildings can be expressed as a multiple of the arşın, but although their measurements may vary depending on the construction materials used, the dimensions remain within the scale given by the unit of measurement.

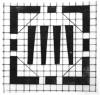

The aforementioned correspondence enables us to reconstruct the properties of the formerly existing documentation, for which a rare 16th century Ottoman document can serve as an analogy. For a design of the whole building prepared on a square grid network, an archival drawn document from the first half of the 16th century preserved in the archives of the Topkapi Museum can be considered as an example. The drawing depicts three versions of the shrine designed for Abdal Ata, Emir Seyyid, Redjeb and Burhan (Bermekan) Dede. Source: [3], published: [4]; [5]; [6]. (Figure 3) The floor plan supposedly created for decision making was could also be used in the course of the construction (karname). It represents the design process of the Bektashi türbe in the village of Çorum, with three possible versions, each constructed on a 10 x 10 module grid system.

The use of the historical unit and the drawn documentation in Hungary is confirmed by two archival sources in Ottoman language. One source is about the activity of the provincial architect in Buda (Budin Mimari), and describes the architectural features of the conversion of the Virgin Mary Church into a mosque [7] [8]. The provincial architect discussed matters with the imperial chief master through the mediation of the kadi. At the same time, there is a written evidence of a draft drawing (resm) for the governor general of Buda to prepare a drawing of the castle of Szigetvár to be sent to the court for approval. [1] The aforementioned historical Ottoman unit of measurement was recorded in the 16th century in the letter of a foundation by Mustafa pasha, the governor-general of Buda (Budin’de merhum Mustafa Paşa'nın Vakıfnâmesi). [9] All these prove that architectural drawings and architectural principles used in the imperial center were also applied in the territory of Hungary.

Consequently, the shrines, which were built during the period of Ottoman occupation in the 15–16th Centuries, were designed and recorded in a similar method which was recorded in the aforementioned written and drawn form. [S3]

The methodology outlined in the previous theses, which establish correspondence between the dimensions of the buildings, the documentation method of 15th–16th centuries, and unit of measurement, can be tested on the shrine of Süleyman Sultan. In recent years, the exact locations of the shrine and its building complex (mosque, cloister-tekke and palisade-palanka) have been identified by an international and interdisciplinary research team, [10] and at the same time, its basal walls have been excavated. [11] The building, built on the former area of the sultan’s tent and over the buried organs of the Emperor, was a square planned structure covered by a dome with a three-part porch roof (son cemaat yeri). Its basic structural walls are brick and stone, with wooden beam lines. The contour drawn on the survey documentation of the excavated shrine is also coherent with the modular grid system of arşın units; therefore, the determining structural and spatial dimensions of the türbe can be expressed as multiple units of the historical measurement. (Figure 4)

|

Figure 2: The proportions of the shrine of Gül Baba in Buda. The horizontal section of the model captured with TLS equipment taken on the height of the lower windows with the arsin module grid system. The figure is directed to north. The survey and drawing was made by Gergő Máté Kovács, 2019. Click on the picture! |

Figure 2: The proportions of the shrine of Idris Baba in Pécs. The horizontal section of the model captured with TLS equipment taken on the height of the lower windows with the arsin module grid system. The figure is directed to north. The survey was made by Krisztina Fehér and Gergő Máté Kovács, the drawing was made by Gergő Máté Kovács, 2019. Click on the picture! |

Figure 3: One drawing of the three plan versions of the türbe of Abdal ʿAṭa, Emir Seyyid, Receb, and Burqan (Bermekan) Dede with the modular grid system. Source: [3], published: [4]; [5]; [6]. Click on the picture! |

Figure 4: The contour of the base of the walls of the türbe (shrine) of Sultan Suleiman in Szigetvár-Turbék-Szőlőhegy, with the red colored module grid of arşın units. The drawing was made according to the excavation documentation of Erika Hancz and Béla Simon titled “Plan of the excavated building in Szigetvár-Turbék-Alsóhegy”. Source of the plan used as the basis of the research: [11] page 95. figure 4. Click on the picture! |

Expected impact and further research

The aforementioned methodology which establishes correspondence between the measures of the buildings and the documentation method of 15–16th centuries can provide historical contribution to the identification of undiscovered remains to be excavated in the future. If the aforementioned regularity can be detected on the wall construction, it can help determine the Ottoman origin. The dimensional correlations can contribute to the restitution of the building.

The aforementioned regularity has been examined with a specific functional group: the shrines (türbe or mausolea). Thus, the methodology can be researched in further functional types (for example, baths (hamam, ılıca and kaplıca), or prayer halls (mosque and djami).

The research focused on the territory of Hungary as well as on its southern neighborhood (Syrmia and Belgrade). [S4] Therefore, the research can be continued on further areas of the Ottoman Empire in both central and peripheral locations.

Publications, references, links

List of corresponding own publications:

S1. KOVÁCS, M. G.–RABB, P. (2018) The Evaluation of the Ottoman Memorial Architecture in Hungary. in Mustafa Hatipler (ed.) International Ottoman Traces Symposium, Proceedings, (November 01-02, 2018 Edirne / Turkey) Trakya University, Edirne. (ISBN: 978-975-374-337-6) 241–252.

S2. KOVÁCS, M. G.–RABB, P. (2020) The Preservation of Ottoman Monuments in Hungary –Historical Overview and Present Works. International Journal of Islamic Architecture (9.) 1. – in press

S3. KOVÁCS, M. G.–RABB, P. (2019) The Dimensions of Türbes in Ottoman Hungary. Contributions to the Methods of Ottoman Construction Practices in the Sixteenth Century – in press

S4. KOVÁCS, M. G.–RABB, P. (2016) Belgrád oszmán építészete - a Balkánon jellemző analógiák elterjedésének kortárs kutatásai tükrében [The Ottoman Architecture of Belgrade. According to the Contemporary Researches of the Typical Analogues of the Balkans], Architectura Hungariae 15 (1) 81–91.

List of references:

1. BOA, MD. 23, p. 30, #58, (25. Ca. 981) Republic of Turkey, Ottoman Archives, Istanbul [T.C. Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi]: The commandment to the governor-general of Buda with the direction to a drawing (resm) shall be prepared about the fortification of Szigetvár, which shall be sent for approval to the court, Mühimme Defterleri, No: 23, Commandment no. 58. Date: 25. Cemâziyelevvel 981.

2. TKSM YY. 339. fol. 1r–87v. The Archives of Topkapi Palace Museum, Istanbul [Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi Arşivi]: Risāle-i Miʿmāriyye (Published: CRANE, H. (1987) Risāle-i Miʿmāriyye. An Early-Seventeenth-Century Ottoman Treatise on Architecture. Facsimile with Translation and Notes by Howard Crane, in: Studies in Islamic Art and Architecture, Supplements to Muqarnas. Vol I. Brill, Leiden.)

3. TKSM E.9495/11. The Archives of Topkapi Palace Museum, Istanbul [Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi Arşivi]: Abdál Ata, Emír Szejjid, Redzseb és Burhán (Bermekán) Dede számára, Çorum településére készült türbe három változatának rajza, 16. század

4. ÜNSAL, B. (1963) Topkapı Sarayı Arşivinde Bulunan Mimari Planlar Üzerine [On the Architectural Plans of the Topkapi Palace Archives]. Türk Sanat Tarihi Araştırma ve İncelemeleri [Researches and Studies and Examinations of the Turkish Art History], 1, 189–190.

5. ORGUN, M. Z. (1938) Hassa Mimarları [Imperial Architects], Arkitekt, 12, 336.

6. NECİPOĞLU, G. (2005) The Age of Sinan. Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire, Reaktion Books, London. 169–171.

7. NECİPOĞLU, G. (2005) The Age of Sinan. Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire, Reaktion Books, London. 160.

8. BOA, KK. 67, (5. M. 980) Republic of Turkey, Ottoman Archives, Istanbul [T.C. Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi]: Kamil Kepeci (Divan-ı Hümayun Divan Kalemi) KK.d Genel no: 7537, özel no: 116. Date: 5. Muharrem 980.

9. TS.MA.d, 7000, p. 10., 2nd line; Republic of Turkey, Ottoman Archives, Istanbul [Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi Arşivi]: “The Document of the Foundation of the deceased Mustafa Pasha” (Budin’de merhum Mustafa Paşa’nın Vakıfnâmesi), From: SCHMIDT, A.- SZ. SIMON, É.– YILDIZTAŞ M. ed. (2016) Török-magyar kapcsolatok az Oszmán Birodalomtól napjainkig a levéltári dokumentumok tükrében. – Arşiv belgelerine göre Osmanlı’dan günümüze Türk-Macar ilişkileri. [Turkish-Hungarian Relations from the Ottoman Empire to our Present Days according to Archive Resources] Başbakanlık Devlet Arşivleri Genel Müdürlüğü, İstanbul. 133.

10. PAP, N., FODOR, P. (2017) Szulejmán Szultán Szigetváron. A szigetvári kutatások 2013-2016 között. [Sultan Süleyman in Szigetvár. The Researches in Szigetvár between 2013-2016.] Hungarian Academy of Sciences - University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary.

11. HANCZ, E. (2017) Nagy Szulejmán Szultán szigetvári türbe-palánkjának régészeti feltárása (2015-2016). [Archaeological Excavations of the Türbe-Palisade of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent (2015-2016).] In: Pap, N.–Fodor, P. (ed.) Szulejmán Szultán Szigetváron. A szigetvári kutatások 2013–2016 között. [Sultan Süleyman in Szigetvár. The Researches in Szigetvár between 2013–2016.] Hungarian Academy of Sciences - University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary 131–162.