|

|

BMe Research Grant |

|

Pál Csonka Doctoral School of Architecture

Department of Urban Planning and Design

Supervisor: Dr. BENKŐ Melinda

Functional diversification of large housing estates

Introducing the research area

Large housing estates (LHEs) are a housing typology that originated in Europe in the mid-XX century as a response to the post-WWII housing shortage, employment-driven migration, and the general need for modernization of the living urban space. In Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), however, it was also a political instrument of communist regimes to form a new society and, therefore became a fundamental component of modern planned cities.[1] Such was the case among others in Hungary and Ukraine, where in the 1950s and 60s LHEs became a dominating housing typology in cities (Figure 1). Today, more than 30 years after the change of political regime these socialist housing complexes find themselves in the new social and economic reality, therefore being gradually transformed on architecture and urban levels.[2]

Figure 1. Construction of prefabricated LHE of Kelenföld in Budapest in 1971. (Source: Fortepan.hu 2022)

Brief introduction of the research place

The Department of Urban Planning and Design connects the fields of environmental design (architecture, landscape architecture, engineering, etc.) and the scope of the analytic experts (sociologist, economist, historian, etc.) Its goal is to synthesize the architectural and urban planning approach and to transmit the European culture of fruitful cooperation of various professional fields.

History and context of the research

Large housing estates being part of the mass housing (general term) are claimed to be the most widespread housing typology of the twentieth century related to modern movements in architecture and urban planning, industrialization, and socialist trends in politics.[3] In Europe, the periodization of mass housing is closely related to the most crucial social and economic raptures of the XX century.[4] Two World Wars were the triggers to boost mass housing development and spread it globally, while the end of the Cold War in 1989 and the subsequent collapse of socialist regimes in Europe triggered post-industrial and post-socialist development of cities with new mixed-use schemes for mass housing.[5] In post-socialist Europe, large housing estates are often those housing complexes that were built under state control by means of prefabrication after WWII between 1960s-late 1980s with at least 2000 housing units.[6] With the ongoing Russia-Ukraine War (2022-…) LHEs are being destroyed in many Ukrainian cities, also experiencing loss of population and main urban functions, and will eventually enter a new phase of post-war renewal. The focus of the dissertation is on the post-WWII LHEs in Hungary and Ukraine and their transformations after 1989 including the phase of the ongoing Russia-Ukraine War (Figure 2). LHEs in Ukraine and Hungary share a common construction period, architecture and urban concept of design, and post-socialist privatization. At the same time, they are usually different in scale (bigger size in Ukraine), have different post-socialist renewal strategies (EU programs in Hungary), different social and physical conditions due to the war in Ukraine.

Figure 2. General timeline of LHEs’ development in Hungary and Ukraine. (Source: author. 2022)

The research goals, open questions

Functional zoning related to the socialist lifestyle of the original plans of LHEs is now being challenged by the rising consumption demands and the general need for modernization. This phenomenon can be called functional diversification. In other words, it is a renewal process that works against the original functional division trying to use the existing advantages (e.g., urban position and infrastructure, green areas, population density, etc.) to shape LHEs as a contemporary mixed-use development.[7] This mixed-use development, however, does not always have a positive impact on the original urban composition of LHEs (Figure 3). Functional diversification is a typical phenomenon for the post-socialist development of LHEs in countries like Hungary and Ukraine. The goal of the research is to create a simple method for the analysis of the LHEs’ urban and architectural renewal based on the typology of their functions, and using the results of this study, develop sustainable strategies for the post-war renewal of LHEs in Ukraine. Budapest LHEs will be taken as a case study example, however, the method used in this research can be applied to other cities and cases. What is the general periodization and terminology of LHEs in Ukraine and Hungary? How did the Russia-Ukraine War influence LHEs in Ukraine? How to create a typology of functions in LHEs? How to classify urban and architectural renewal practices in Budapest LHEs? What strategies of Budapest LHEs post-socialist renewal can be used for the post-war renewal of Ukrainian LHEs, and what not?

Figure 3: New shopping center “IKEA” in the prefabricated housing estate

Füredi úti in Budapest. (Source: Author, 2021)

Methods

In order to understand and compare contemporary architecture and urban transformations of LHEs in different countries (e.g., Ukraine and Hungary) in other words to see their phenomenon of functional diversification in a post-socialist period of development the general typology of functions in LHEs was created. The typology is based on the theoretical framework of Kropf [8] where the urban form is characterized by built and open space elements, therefore we introduced two main morphological categories: the mass and void, and their functional subcategories: residential or public buildings; transport or recreational space.

(Table 1).

|

A. MASS [BUILDINGS] |

B. VOID [OPEN SPACE] |

||

|

A1. Residential |

A2. Public |

B1. Transport |

B2. Recreation |

|

dwelling units and common spaces of the building (staircase, storage, garage, rooftop) |

facilities of the urban infrastructure: stations, parking, or technical buildings |

road system, parking |

playgrounds, sports fields, small green areas between buildings |

|

1st level: primary schools, kindergartens, day nurseries, grocery shops and retail outlets |

|

||

|

2nd level: banks, post offices, culture clubs, special stores, cinemas |

|

green urban park, public space, open-air market, outdoor stadium |

|

|

3rd level: administration buildings, large cultural centers, theatres, and museums. |

|

||

Table 1: Typology of functions in LHEs. (source: Author, 2022)

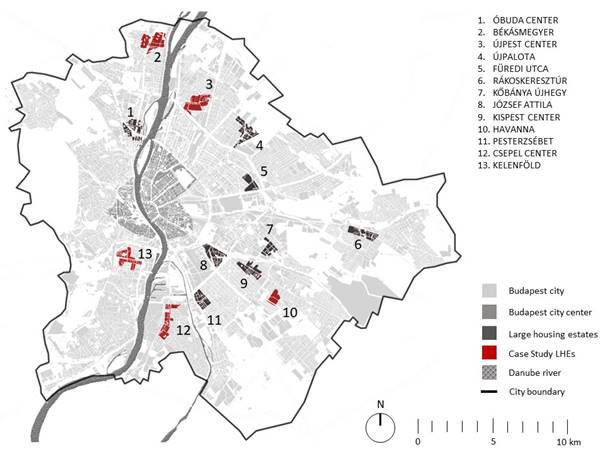

The research uses literature with a multidisciplinary approach, and analyses planning documents and case studies from Budapest. There are 13 LHEs in Budapest with more than 20,000 inhabitants. All of them were built in various parts of the city (but not in the historic center), during two 15-year mass housing programs between 1960 and 1990 as high-density modern neighborhoods. While the research gives general information about all LHEs in Budapest, the in-depth case studies are performed in five of them (Figure 4) - Csepel (1948–1982), Kelenföld (1965–1983), Békásmegyer (1971–1983), Újpest (1974–1986), and Havanna (1977–1985). These case studies are introduced to assess the developed typology and to see how the LHEs’ functions changed over time by using local documents and fieldwork methods in architecture: mapping, morphological analysis, and photo making. On the other hand, the effects of the war on the actual situation of LHEs in Ukraine are studied by means of open-source data about the destruction and surveys with residents of these estates. Based on the data gained about the actual situation of LHEs in Ukraine and case study examples from Budapest that showcase a steady post-socialist renewal process, we can state what strategies can be used for postwar renewal in Ukraine.

Figure 4. Budapest and its 13 LHEs. (Source: author, 2023)

Results

1) Post-socialist and post-war renewal in Ukraine. According to KSE (Kyiv School of Economy)[9], most of the war destruction is related to residential funds and social infrastructure, which are the key functional elements of LHEs (Figure 5). At the same time, many of the pre-war problems of LHEs have only been strengthened. They are as follows: bad physical condition of housing, public buildings, transport infrastructure, and some open space functions; reduction of public functions or their absence; monofunctional green open space, inefficiency of public transport. As a result, due to the increased relevance of LHEs as an existing urban housing in Ukraine, centralized strategies must be developed for their post-war renewal. These strategies can be acquired by case study analysis from other post-socialist countries and cities, like Budapest (Hungary), where the functional diversification process has a steady character.

Figure 5. Destroyed residential building in one of the LHEs in Zaporizha, Ukraine. (Source: Suspilne news agency)

2) Functional typology. The research created a general typology of functions in LHEs that can be applied in various countries to analyze their physical and functional transformations.

3) Residential buildings. This is the main function of LHEs. The majority of buildings are socialist time panel houses that need renovation under the general design approach, co-funded by the government with the participation of residents. Panel buildings also require functional diversification of the ground floors, common spaces, and roofs. At the same time, new residential construction (Figure 6) has to be encouraged but regulated by sustainable housing policies. New mixed-use, social cooperative housing can significantly increase the livability of LHEs.

Figure 6. New housing development in Kelenföld LHE, Budapest. (Source: Author, 2021)

4) Public buildings. LHEs have a well-defined functional structure with a sufficient amount of basic (1st level) functions inherited from socialist times. However, many of these buildings are outdated and need to be diversified functionally and architecturally. Public functions of the 2nd and 3rd levels are public centers of district and/or city level, which have to become multipurpose spaces or community centers with appropriate design solutions well-positioned in the estate with direct access to public transport (Figure 7).

Figure 7. New mixed-use market area in Békásmegyer LHE. (Author: Zsolt Hlinka, 2019)

5) Transport. The transport function is the backbone of LHE's urban structure that creates the system of streets and roads to form urban blocks. Most of the LHEs were created on the periphery of the city, therefore they heavily rely on public transport (Figure 8). This goal can be achieved by a robust system of public and private transport. Within the estates, means of alternative transport (cycling, electric scooters, and car sharing) as well as walkability have to be increased. Parking areas have to be minimized and possibly relocated to the underground or parking building spaces.

Figure 8. Transport hub of Kelenföld railway station next to Kelenföld LHE. (Source: Futureal[10], 2022)

6) Recreation open space. Open space in LHEs is a linking element for the built functions. On the one hand, it plays the role of a “green park”, and on the other contains important urban outdoor functions for recreation. Its green character is also one of the strongest assets of LHEs when it comes to the evaluation of their sustainability. The landscape of LHEs provides for high surface permeability, creates green infrastructure, and forest/natural continuity. These important qualities have to be maintained and strengthened. Above that high land use mix and diversification of recreation functions for residents must be developed (Figure 9). Big open spaces like district parks and boulevards have to be the most attractive and functionally complex areas, which increase the importance of the estate on the city level, and therefore boost its attractiveness for investment and relocation.

Figure 9: Újpest LHE sports and recreation space. (Source: Author, 2020)

Expected impact and further research

The research provides a general typology of functional elements to analyze large housing estates. This typology is evaluated on case studies in Budapest. Its results are systemized to provide strategies for the post-war reconstruction of LHEs in Ukraine, based on the actual data on the destruction and social impact of the War. It is also useful to understand problems in LHEs in Budapest and provide means to improve its main functions. Moreover, it is expected that the same method can be used to analyze case studies in other countries and cities to collect more practices for the renewal process of LHEs in Europe.

Related published papers

[1] Losonczy, A., Balla, R., Antypenko H., Benko, M. (2020) “Re-Shaping Budapest: Large Housing Estates and their (un)Planned Centers” ARCHITEKTURA AND URBANIZMUS 54(1–2).

[2] Antypenko, H., (2019). Kharkiv Mass Housing Estates: Socialist Past and Post-Socialist Present. Doconf19 conference proceedings.

[3] Benko, M., Antypenko, H. Losonczy A. (2020) “Contemporary food markets within Budapest’s large housing estates: influencing factors of the design process”, ALFA journal by the Faculty of Architecture of the Slovak University of Technology.

[4] Antypenko, H. Benko, M. (2020) "Mass housing estates in Csepel, Budapest: urban form evaluation in relation to sustainability", Belgrade "Places and technologies" conference proceedings.

[5] Antypenko H., Antonenko N., Didenko K. (2021) “Urban Transformations of Kharkiv’s Large Housing Estates – Novi Budynky and Pavlovo Pole After 1991”, Építés – Építészettudomány journal.

[6] Antypenko H., Benko M., (2022) “Architectural and urban transformations of Large Housing estates related to functional diversification: the case of Kelenföld in Budapest”. Vilnues Journal of Architecture and Urbanism. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3846/jau.2022.17462

[7] Egedy, T., Szabó, B., Antypenko, H., & Benkő, M (2022) “Planning and Architecture as Determining Influences on the Housing Market: Budapest – Csepel’s Post–War Housing Estates” Urban Planning Volume 7, Issue 4, Pages 325–338, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v7i4.5771

References

[1] Power, A. (1997). Estates on the edge: The social consequences of mass housing in Northern Europe. Palgrave Macmillan.

[2] Murie, A., van Kempen, R., & Knorr-Siedow, T. (2003). Large housing estates in Europe, general developments, and theoretical background (RESTATE Report). Utrecht University.

[3] Florian, U. (2012). Tower and Slab: Histories of Global Mass Housing. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203804131

[4] Glendining, M. (2021). Mass Housing: Modern Architecture and State Power – a Global History. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

[5] Neducin, D., Škoric, M., & Krkljes, M. (2019). Post-socialist development and rehabilitation of large housing estates in Central and Eastern Europe: A review. Tehnički vjesnik, 26(6), 1853–1860. https://doi.org/10.17559/TV-20181015174733

[6] Hess, D. B., Tammaru, T., & van Ham, M. (2018). Lessons learned from a pan‐European study of large housing estates: Origin, trajectories of change and future prospects. In D. B. Hess, T. Tammaru, & M. van Ham (Eds.), Housing estates in Europe: Poverty, ethnic segregation, and policy challenges (pp. 4–31). Springer.

[7] Hirt, S. (2012). Mixed Use by Default: How the Europeans (don’t) Zone. Journal of Planning Literature, 27(4), 375–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412212451029

[8] Kropf, K. (2014). Ambiguity in the definition of built form. Urban Morphology, 18(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.51347/jum.v18i1.3995

[9] Damaged in UA (2023). https://damaged.in.ua/damage-assessment

[10] Futureal (2022). https://www.futurealgroup.com/hu/projects/etele-plaza/