|

BMe Research Grant |

|

BME Doctoral School of Psychology

Department of Cognitive Sciences

Supervisor: Prof. Dr. István Winkler

The Levels of Resiliency: From Perception to Personality

Introducing the research area

It is assumed that the most important dimensions of personality (the Big Five traits) do not change from adolescence to adulthood, or just a little. Although this implies a stable behavioral system, beyond stability, however, it is plasticity or resiliency that can ground the adaptivity of behavior. In our previous study (Farkas & Orosz, 2013) we found that the personality traits which do not show a considerable change over six years (i.e. extraversion, Costa & McCrae, 1988) can change in ten minutes if the individual is resilient. In the future I would like to discover how this kind of plasticity appears at the more basic levels of behavior, like perception. Moreover, my aim is to examine whether the individual differences in auditory multistable perception (Denham et al., in preparation) are modality-specific or general, and if these individual patterns appear at higher organizational levels of personality like creativity.

Brief introduction of the research place

My research is conducted under the supervision of Prof. Dr. István Winkler at the Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience and Psychology, Research Centre for Natural Sciences, Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Our research group’s main profile is auditory research with cognitive and neuroscientific methods. In this group, I do my own research on the individual differences in perception and behavior and their relationship with resiliency.

History and context of the research

The best way to describe a creative individual is through paradoxes (Csíkszentmihalyi, 1996). Good scientists can also behave introverted when researching literature or when analyzing data, however, to be truly successful, they must be extraverted when presenting at conferences. Plasticity enables different behaviors which can be contradictory at first sight. Block (1965, 2002) called this plasticity ego-resiliency, a dynamic capacity systematically modifying the level of control to optimize behavior and personality to match the demands of the environment. Ego-resiliency can be defined along a continuum in which individuals differ from each other: ego-resilient individuals have good problem solving skills and they can highly adapt to the demands from the environment, while ego-brittle individuals tend to perseverate in their behavior.

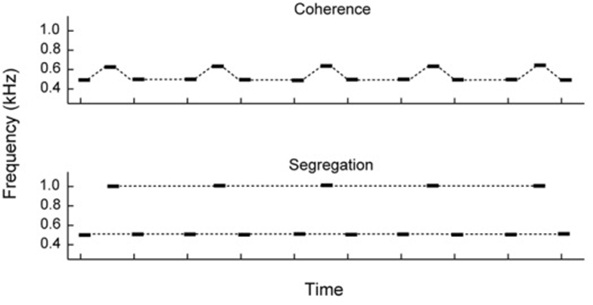

Figure 1. The two most prominent percept of the ABA- sound sequences: integration (above) and segregation (below) (Snyder, Gregg, Weintraub & Alain, 2012)

Figure 2. A version of the duck-rabbit illusion – an example for ambiguous figures

Ego-resiliency can potentially grasp the plasticity between low (i.e. identifying auditory objects) and high level (i.e. creativity) cognitive functions. In the case of auditory objects, if an ABA- sound sequence is presented with constant physical properties the perception of individuals switches between two percepts: they hear one sequence (ABA-, integrated percept) or two sequences (A and B separately, segregated percept, Figure 1). This shows a similar pattern as experienced with ambiguous figures (Figure 2). The individual seeing the images can switch between possible percepts (seeing Figure 2 as a duck or a rabbit).

Recent results (Denham et al., in preparation) show that there are distinct individual patterns in listening to this kind of auditory stimuli. According to a recent theory (Gabora, 2010) creativity can be defined as the flexible utilization of abstract and analytical thinking. The ability to switch between the different percept of ambiguous figures is linked to creativity (Wiseman et al., 2011). This underlies the importance of discovering the relationship between the individual differences in perception, ego-resiliency and creativity.

The research goal, open questions

The main purpose of this study is to identify a general model of individual differences in behavioral and perceptual changes at different levels and modalities. We assume that individual switching patterns exist and that these patterns can explain behavior at several levels from perception to creativity. The second aim of the study is to grasp the nature of the switching through plasticity, which is a basic characteristic of personality. We assume that individual differences in plasticity can affect individual patterns of switching, in a way that highly resilient individuals can switch more easily and more often, thus they can adapt better to the demands of the environment.

Methods

We use many different methods for data collection. We use questionnaires to measure characteristics of the personality organization which are hard to observe and measure in other ways. The most important scale is our version of Block and Kremen’s (1996) ego-resiliency scale. Compared to the original, our version can measure three different components of resiliency separate. We test the validity of our scales through Structural Equitation Modeling (Brown, 2006).

In order to create extraverted and introverted contexts, we utilize tasks used in social psychology (i.e. prisoner’s dilemma, see Myerson, 1991) and decision making tasks (i.e. Game of Dice Task, Brand et al., 2005). For auditory ambiguity, we use the stimuli from Denham et al.’s (in preparation) study. For visual stimuli, we use figures similar to the duck-rabbit illusion (Figure 2). To measure creativity, we use multiple instruments like Guildford’s (1967) Alternative Uses Task, in which participants have to name as many as possible alternative uses of everyday objects in a short period of time.

Of the neuroscientific methods, we use electroencephalography (EEG) measuring the brain’s electric activity and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS). We plan to collect and analyze EEG data on the basis of functional network analysis (van Straaten & Stam, 2011). This conceptualizes and examines the brain as a complex network, and maps functional nodes and their connections based on the brain’s electrical activity. NIRS uses the absorption and reflection of near-infrared light to measure the concentration of oxy- and deoxyhemoglobin in the brain (Obrig & Villringer, 2003). Through this method, active cortical regions can be localized. The combination of the two methods allows us to identify the nodes and their connections participating in the change between different percepts and behaviors. Thus we can confirm our results about switching and the plasticity required for it, with not only behavioral, but electrophysical and hemodynamical data as well.

Results

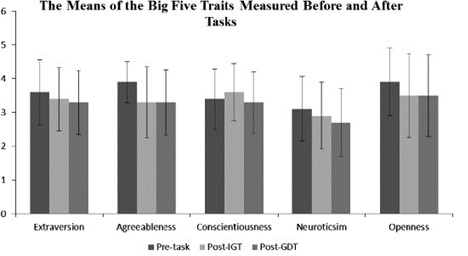

In one of our previous questionnaire based experiments participants filled out a short personality inventory and then participated in two decision making tasks. Then they filled out the same personality inventory again. The results showed that personality dimensions supposed to be temporally stable (i.e. Costa & McCrae, 1988), do differ significantly from each other (Figure 3). This means that extraversion, which measures sociability and social orientation, was significantly lower after a solitary task. Five minutes were enough for this change. What makes this result more interesting is that the extent of this change correlated positively with ego-resiliency. Consequently, ego-resiliency as a trait makes it possible for resilient individuals to organize their behavior adaptively to the demands of the situation and this could be measured on a self-reported scale.

In our recently submitted paper, we discovered three aspects of ego-resiliency. Based on the original theory we named the first active engagement with the world, which regulates information uptake. The second dimension is repertoire of problem solving strategies, which collects skills required for plasticity. The third one is integrated performance under stress, which is responsible for coping with stressful situations. We re-analyzed the previous study based on these three dimensions, and we found that integrated performance under stress dimension does not correlate with the changes on the measured personality dimensions. This is important because the experimental setup was not stressful, so the activity of this component was not needed. In the original theory (Block, 2002) the process leading to the development of plasticity is initiated by an affective response to an internal or external event. However, based on these results, this construct can also function in neutral situations which enables its more general utilization in future studies.

Figure 3. Means and standard deviations of the measured personality dimensions based on the Big Five model (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism and openness) and their change between pre-task and after-task (post-IGT, post-GDT) conditions. Pre- and after-task measurements differ significantly (p < .05) from each other with one exception (conscientiousness pre-task and post-gdt). (Farkas & Orosz, 2013).

Expected impact and further research

In the short term, we plan to extend our earlier study on the changes in personality dimensions (Farkas & Orosz, 2013) to include extraverted contexts as well. We assume that self-reported personality dimensions will change according to the opposing contexts and that their magnitude will correlate with resiliency. Moreover, we will start the data collection for our study about the relationship between auditory and visual ambiguities and creativity.

The studies using questionnaires usually ignore plasticity and context-dependency and related researches are marginalized. However, they (i.e. Mischel & Shoda, 1995) use a completely different methodology, therefore, direct comparison between their results and the mainstream is troublesome. We would be able demonstrate this marginalized perspective in personality research using the methodology of the mainstream with all of its requirements of validity and reliability which can have great impact in future papers.

If we managed to discover stable and modality-independent individual differences in perceptual ambiguities, that could create new perspectives in the research of individual differences. Furthermore, if the individual patterns are connected to high level processes like creativity or ego-resiliency, it can contribute to the discovery of a general organization principle in behavior.

Publications, references, links

Related paper

Farkas, D., & Orosz, G. (2013), The link between ego-resiliency and changes in Big Five traits after decision making: The case of extraversion. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(4), 440-445. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.04.003.

References

Block, J. (1965), The challenge of response sets: Unconfounding meaning, acquiescence, and social desirability in the MMPI. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Block, J. (2002), Personality as an affect-processing system. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Block, J., & Kremen, A. M. (1996), IQ and ego-resiliency: Conceptual and empirical

connections and separateness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(2), pp. 349-361. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.349

Brand, M., Fujirawa, E., Borsutzky, S., Kalbe, E., Kessler, J., & Markowitsch, H. J. (2005), Decision making deficits of Korsakoff patients in a new gambling task with explicit rules: Associations with executive functions. Neuropsychology, 19(3), pp. 267–277. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.3.267

Brown, T. A. (2006), Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: Guilford.

Costa, P., & McCrae, R. (1988), Personality in adulthood: A six-year longitudinal study of self-reports and spouse ratings on the NEO Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(5), pp. 853–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.853

Csíkszentmihalyi, Mihály (1996), Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York: Harper Perennial.

Denham, S. L., Bőhm, T., Bendixen, A., Szalárdy, O., Kocsis, Zs., & Winkler, I. (előkészületben), Stable individual characteristics in the perception of multistable auditory stimuli. Frontiers in Neuroscience.

Gabora, L. (2010), Revenge of the “neurds”: Characterizing creative thought in terms of the structure and dynamics of memory. Creativity Research Journal, 22(1), 1-13. doi: 10.1080/10400410903579494

Guilford, J. P. (1967), The nature of human intelligence. New York: McGraw-Hil

Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (1995), A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychological Review, 102(2), pp. 246-268. doi: 10.1037//0033-295X.102.2.246

Myerson, R. B. (1991), Game theory: Analysis of conflict. Boston, MA.: Harvard University Press.

Obrig, H., & Villringer, A. (2003), Beyond the visible: Imaging the human brain. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism, 23, 1-18. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000043472.45775.29

Snyder, J. S., Gregg, M. K., Weintraub, D. M., & Alain, C. (2012), Attention, awareness, and the perception of auditory scenes. Frontiers in Consciousness Research, 3. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00015

van Straaten, E. C. W., & Stam, C. J. (2013), Structure out of chaos: Functional brain network analysis with EEG, MEG, and functional MRI. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 23(1), 7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.10.010.

Wiseman, R., Watt, C., Gilhooly, K., & Georgiou, G. (2011), Creativity and ease of ambiguous figural reversal. British Journal of Psychology, 102(3), pp. 615–622. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.2011.02031.x